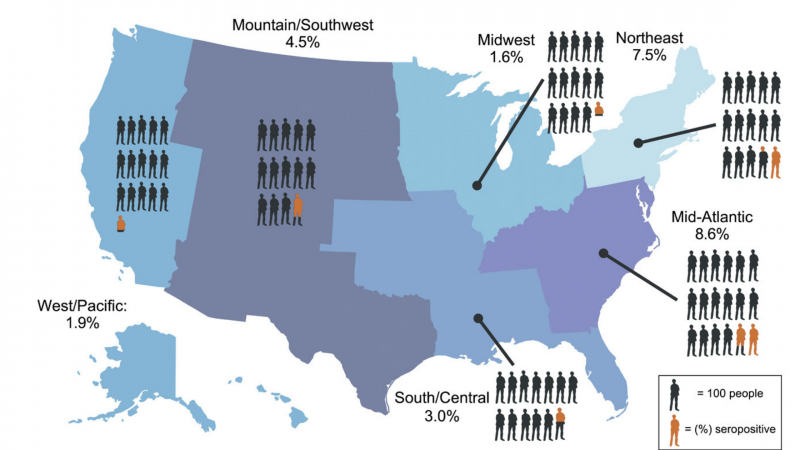

In a recent study that sought to measure antibody prevalence in participants who had not previously been diagnosed with a SARS-CoV-2 infection, a team of National Institutes of Health researchers reported that for every person diagnosed with COVID-19 in the spring and summer of 2020, it’s estimated that five additional people infected with the virus went undiagnosed. This represents nearly 17 million undiagnosed cases by July 2020. According to a NIH press release, results of this study help demonstrate how quickly SARS-CoV-2 spread.

“Our team assumed there was some level of undiagnosed COVID infection early on in the pandemic because testing wasn’t widely available and also because there was a lack of appropriate laboratory quality standards,” said Dominic Esposito, Ph.D., an author on the study and director of the Protein Expression Laboratory at the Frederick National Laboratory.

The Protein Expression Laboratory is funded by the RAS Initiative and was able to pivot its existing technology and infrastructure to COVID-19 research. Working with colleagues across the National Institutes of Health, Esposito and his team provided key proteins for the COVID-19 antibody tests used in the study.

The FNL team consisted of Matt Drew, Kelly Snead, Jennifer Mehalko, Vanessa Wall, J-P Denson, Peter Frank, Simon Messing, and Bill Gillette. Esposito said it is the best collaboration he’s been a part of in his 20 years at the national laboratory.

“This study is unique because it cuts across three separate NIH institutes,” including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering Esposito, said. “To be able to take the expertise from different groups and put it together into a project like this – it was a great collaboration.”

‘Churning out proteins’

The large quantity of antibody tests needed for the study’s 11,382 participants required a plethora of proteins to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in blood samples.

“It’s a great demonstration of what FNL can do,” Esposito said. “We have technologies needed for this work that other organizations do not, and I think each component of the collaboration was vital to the performance of this project.”

Prior to the pandemic, Esposito said an average protein production in his group resulted in about 10 milligrams of purified protein. He said they have produced more than 2 grams of SARS-CoV-2 proteins since March 2020.

“For a research and development lab, it’s pretty impressive,” Esposito said.

Study shows unexpected response rate, data

Samples were collected from 8,058 of the participants. Esposito said the researchers initially worried whether the study would obtain enough participants for the results to be statistically significant.

“As we saw the data start coming in, we realized that it was going to be highly significant,” Esposito said. “Many people told us that we were too optimistic, that we were never going to get that amount of people to participate. The fact that we got 11,000 participants to sign up and more than 70% of them to return samples was very exciting.”

In addition to the initial blood draw and data collection from participants, researchers are following up at six months and 12 months. The new assays at these timepoints also will include SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein to ensure the antibody tests will detect positive cases in vaccinated individuals. During this follow-up study, scientists will evaluate how long people who had asymptomatic infections continue to have an antibody response.

Communication and flexibility spark success

Communication has been vital to the study’s success, Esposito said. Team leaders met each week and operated on tighter timelines than before the pandemic. As soon as proteins were delivered to partner laboratories, they were quickly added to assay plates.

Esposito and his team adjusted to new schedules and adapted to restrictions due to the pandemic, working around the clock to produce high-quality proteins. Flexible leadership at FNL and the National Cancer Institute enabled Esposito to handle other needs as they arose. For example, Esposito and his team were able to deliver proteins to NIAID to support serology testing of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

“Our usual work is fairly far from the clinic, but the pandemic really brought home to people what we are working on. It has a lot of real-world value in understanding the dynamics of the pandemic and understanding the potential thresholds for herd immunity,” Esposito said.

Biotechnology that’s here to stay

Initially, the team was focused on four versions of two different proteins: the spike protein and the receptor binding domain (RBD). The goal of the project was to take the four different versions of these two proteins and determine which worked best in the assay. Since then, Esposito and his team have made every variant of concern of spike and RBD that has been identified.

Esposito said he and his team have learned invaluable information from their pandemic work and will continue to do so with the six-and 12-month follow up. The Protein Expression Laboratory is now set up for large-scale mammalian production and it has implemented the use of magnetic beads for protein purification.

“Our COVID work has refocused us in the sense that we were able to develop new technologies,” Esposito said. “Because of this, we can now use this new technology for other parts of our work.”

The image shows geographic distribution of undiagnosed seropositivity in the United States from May to July 2020. Figure first appeared in Science Translational Medicine.

Media Inquiries

Mary Ellen Hackett

Manager, Communications Office

301-401-8670