Publicly available data sets related to COVID-19 are appearing in an unexpected place—the Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), a project of the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the National Cancer Institute.

Since the start of the pandemic, researchers around the world have been racing to learn as much as possible about the virus—how it spreads, how to diagnose and treat it, and how to develop vaccines against it. One way to help speed up scientific discovery is data sharing.

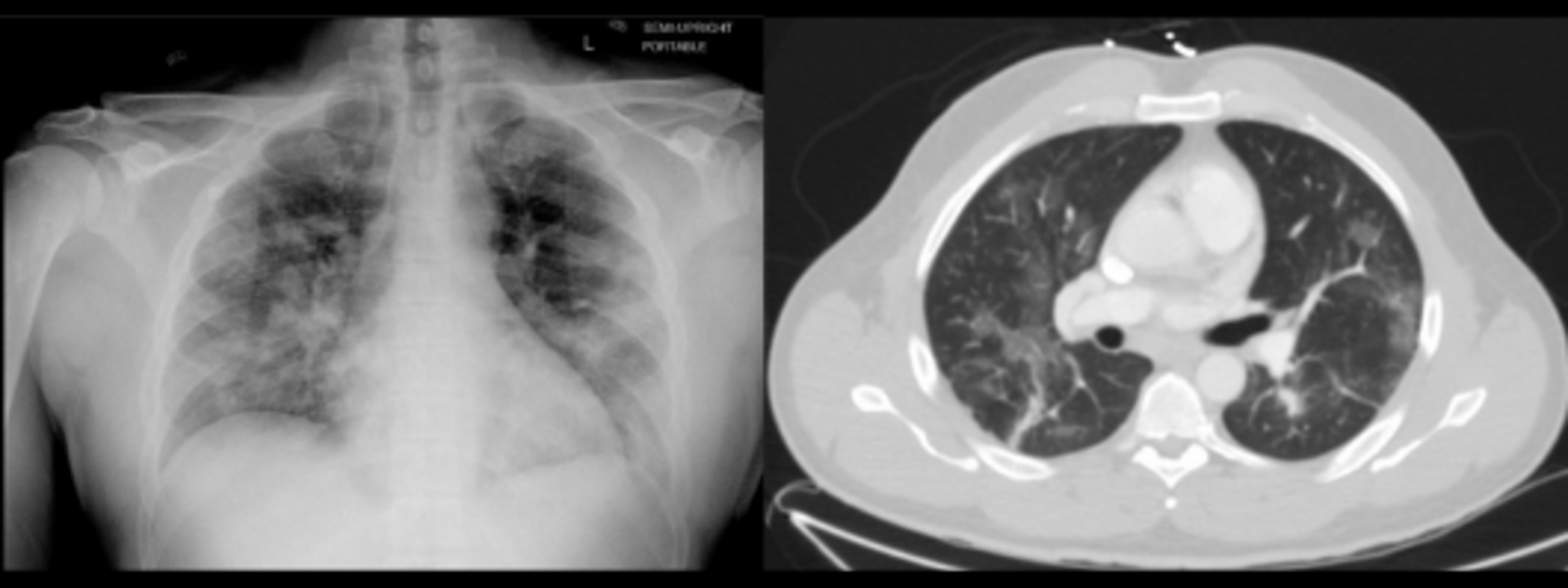

A sample image from a COVID-19 data set on TCIA. Chest radiograph (left) and Computed Tomography image (right) of the same patient taken one day apart. Patchy bilateral ground-glass/consolidative opacities are seen in both lungs.

The Cancer Imaging Informatics Lab at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (FNL), a team providing informatics support to the Cancer Imaging Program, is leveraging its flagship program, TCIA, to do its part. Researchers approached the group during the height of the pandemic, seeking to share COVID-19 data as quickly as possible.

“When the pandemic really started to kick into high gear and all these different people had this realization of ‘oh, maybe imaging can help,’ we immediately started to get solicitations from a number of different groups saying, ‘We want to work on this project. Can you help us get the data out there to the community?’” said Justin Kirby, project manager in FNL’s Applied and Developmental Research Directorate, who oversees TCIA data curation activities.

TCIA quickly pivoted to sharing COVID-19 data sets because it has an established, fine-tuned process to handle large volumes of radiological imaging data—often containing special formatting and thousands of tags from hospital and health center picture archiving systems—and prepare it to be posted in a unified, understandable way.

Part of this process involves removing patient-identifying information, in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This is a big concern and barrier for many researchers seeking to share their data. A researcher’s institution can have more confidence in releasing the images to be posted on TCIA because of the team’s experience in handling such sensitive data.

All told, TCIA was a perfect place to rapidly share COVID-19 data during the pandemic.

The group at FNL helps establish the boundaries of the project and conducts outreach after the data are posted to let researchers working in the field know it is available. When the requests for sharing COVID-19 imaging data sets started coming in, the TCIA team received permission from NCI to allocate some of its resources toward COVID-19-related data sets. They selected several COVID-19 imaging projects to support through a proposal process.

“Ultimately, it was decided that even though supporting cancer research is our usual mandate … this pandemic is making everyone’s lives miserable, so if there’s anything we can do to help, we should try to do it,” said Kirby.

They’re making sound progress.

Data helping computers learn

In addition to providing useful information for researchers studying the virus, the publicly available data sets allow access for computer scientists developing algorithms to analyze the data or training software to detect COVID-19 infection.

One data set compiled by a multidisciplinary, multinational team includes chest CT scans of patients with COVID-19 infections. Since it was posted to TCIA, scientists have been busy putting it to good use.

Some researchers have used the data set to train artificial intelligence to detect COVID-19 pneumonia from chest CT scans, with 90.8% accuracy. Computational scientists put patient images through a series of deep-learning algorithms and “trained” them to correctly identify the lungs with lesions caused by COVID-19.

A computing segmentation challenge invited respondents to use the data set to discover new methods of distinguishing COVID-19 from other types of lung ailments. An American high school student was a top-10 finalist in the competition, organized by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Children’s National and NVIDIA, a high-performance computing and artificial intelligence company.

NVIDIA also partnered with NIH to develop an AI application that can detect the probability a patient has COVID-19 from a lung CT scan, trained, in part, with this data set.

Supplying unique data sets

This COVID-19 data set is one of four that TCIA worked on since the start of the pandemic. Each offers distinct advantages.

For instance, RICORD has several parts and is a collaboration of the Radiological Society of America and others. It includes a set of CT scans from patients who tested positive for COVID-19, a control set for patients who received scans but tested negative for the virus, and a set of chest X-rays from patients who have COVID-19. Several of these include expert annotations and labels.

“That’s really important because it gives researchers around the world a sense of what to look for … those labels can also be used by people who are running or testing new algorithms to try to replicate what the experts have found,” said John Freymann, a project manager at FNL who leads the TCIA team.

The RICORD collaboration is building a system similar to TCIA for non-cancer imaging, called the Medical Imaging and Data Resource Center to house their COVID-19 data sets. Sharing the data first through TCIA allowed it to be available sooner, as this system is still being optimized.

A third data set covers a rural population in Arkansas and includes demographics, comorbidities, and other data. It’s also being cross-linked to SARS-CoV-2 cDNA sequence data extracted from clinical isolates from the same population.

The last, forthcoming, is a large data set from Stony Brook University in New York that will include PET-CT, MRI and other types of imaging of multiple organ sites, not just the lungs, along with clinical data for each patient.

Enabling open science

Though TCIA has recently pivoted some of its efforts toward COVID-19-related imaging data sets, it’s been a valuable cancer imaging resource for scientists since 2010. As of 2020, over 1,000 published papers used data sets from TCIA.

In addition to providing publicly available data, TCIA allows scientists to meet their data-sharing goals and requirements—which are increasingly common—as an “approved repository” for a number of journals, including Springer Nature’s catalogue of journals. Even the NIH has doubled down on its requirements for data sharing, creating stricter requirements that will take effect in 2023.

Providing open-access imaging data can foster rapid scientific progress, and with COVID-19, scientists are more eager than ever to share information so they can work together to fight the virus.

“Ten years ago, you couldn’t say this, but now there’s really an atmosphere of ‘let’s share data; let’s do open science.’ Especially with COVID data, where everyone senses the urgency,” said Freymann.

images contributed by John Freymann (Image originally from The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Translational Research Institute, Department of Radiology, Department of Biomedical Informatics and Department of Surgery, Little Rock, AR.)

Media Inquiries

Mary Ellen Hackett

Manager, Communications Office

301-401-8670